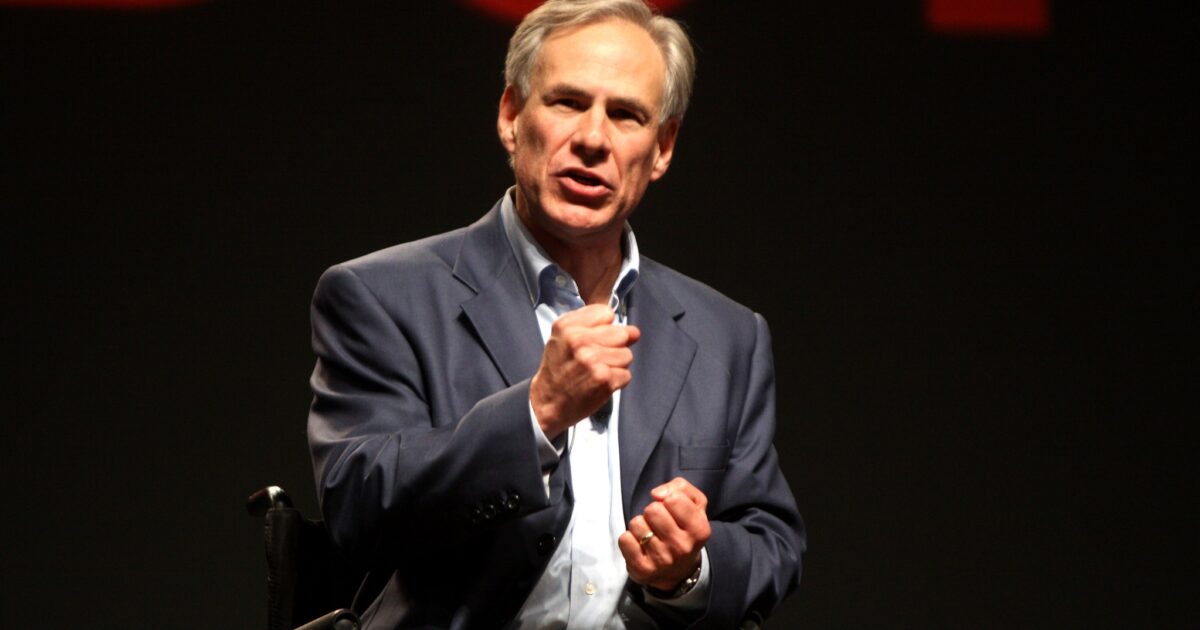

TX – After Texas became the first state to eliminate both its face mask mandate and its business occupancy limits in early March, President Joe Biden said the decision reflected “Neanderthal thinking.” Gilberto Hinojosa, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party, described Gov. Greg Abbott’s order as “extraordinarily dangerous,” warning that it “will kill Texans.”

Anthony Fauci, Biden’s top COVID-19 adviser, said lifting mask mandates “is really quite risky,” because “when you pull back on measures of public health, invariably you’ve seen a surge” in cases and deaths. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said she had a “recurring feeling” of “impending doom,” warning that premature relaxation of “public health prevention strategies” could lead to a “fourth surge.”

More than two months later, the public health disaster predicted by Abbott’s critics has not materialized. A new analysis by three economists confirms that his decision had no discernible impact on COVID-19 cases or deaths in Texas.

“We find no evidence that the Texas reopening led to substantial changes in social mobility, including foot traffic at a wide set of business establishments in Texas,” Bentley University economist Dhaval Dave and his two co-authors report in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper. “We find no evidence that the Texas reopening affected the rate of new COVID-19 cases during the five weeks following the reopening.” They say their findings “underscore the limits of late-pandemic era COVID-19 reopening policies to alter private behavior.”

Dave, San Diego State University economist Joseph Sabia, and SDSU graduate research fellow Samuel Safford looked at smartphone mobility data from SafeGraph and COVID-19 data collected by The New York Times. They compared trends in Texas before and after Abbott’s order took effect on March 10 to trends in a composite of data from other states that retained their COVID-19 restrictions but were otherwise similar.

“We find that the Texas reopening had little impact on stay-at-home behavior or on foot traffic at numerous business locations, including restaurants, bars, entertainment venues, retail establishments, business services, personal care services, and grocery stores,” Dave et al. write. “We find no evidence that the reopening affected the rate of new COVID-19 cases in the five-week period following the reopening. In addition, we find that state-level COVID-19 mortality rates were unaffected by the March 10 reopening.”

Those “null results” were essentially the same in a separate analysis that excluded Austin and Travis County, which maintained local face mask mandates after Abbott lifted the statewide requirement. They also persisted when the researchers compared more urban to less urban counties and when they compared counties where most voters supported Biden in the 2020 election to counties where most voters supported former President Donald Trump, based on prior research indicating that Trump supporters are less likely to wear face masks and follow other COVID-19 safeguards.

Dave et al. suggest several possible reasons why the Texas reopening did not have the impact that its opponents anticipated. First, increasing vaccination (a trend that Abbott’s critics surely were aware of) “may have mitigated the contagion effects of interactions” between members of different households. Second, “it may be that there was limited compliance with and enforcement of mask mandates or capacity constraint requirements prior to the March 10 reopening.” Third, removing occupancy limits, which were previously 75 percent of capacity for most businesses and 50 percent for bars and professional sports, may have been too minor a change to “affect net population-based social mobility and statewide spread of COVID-19.”

Finally, the authors say, “it may be that the types of individuals who

were affected by the policy” were “those least likely to affect the trajectory of COVID-19 growth.” Or perhaps “any increase in social mobility or COVID-19 caused by such individuals was offset by others in the community who engaged in risk avoiding behaviors in response to the reopening.”

It should have been clear when Abbott announced the reopening on March 2 that the changes he planned were unlikely to have much of a direct impact on virus transmission. While he said face masks would no longer be legally required, he urged Texans to continue wearing them in public, and businesses remained free to require them. In Dallas (which may or may not be representative of the state as a whole in this respect), I have not observed any change in business mask policies or customer compliance. And it seemed implausible that removing the 75 percent occupancy cap (the one that applied to most businesses) would have a medically significant effect even in businesses that were frequently butting up against that limit.

Still, it was possible that Abbott’s announcement would affect people’s behavior by changing their risk perceptions. That apparently did not happen either, or at least the effect was not large enough to measurably increase virus transmission. “Even if the initial adoption of restrictions is effective and elicits a population response,” Dave et al. note, “as individuals update their risk assessment and amass information about the pandemic, their behaviors can become highly inelastic over time.”

This study does not prove that lockdowns or less severe COVID-19 restrictions had no initial impact on risky behavior. But it underlines the primacy of private decisions by individuals and businesses.

While there is evidence that stay-at-home orders and mask mandates “were effective in curbing COVID-19 spread early in the U.S. pandemic,” Dave et al. say, “a number of studies have documented that [such interventions] account for a relatively small share of the total variation in individuals’ COVID-19 mitigation behavior.” Those studies indicate that “most of the variation can be attributed to voluntary (non-policy-related) private demand-side responses, likely due to (i) new or updated information on the novel coronavirus, or (ii) changes in individuals’ assessments of contagion risk and developing serious COVID-19 symptoms.”

When it comes to the debate about the costs and benefits of legal restrictions, that observation cuts both ways. “There is evidence that much of the variation in local unemployment during the pandemic is not attributable to lockdown policies, but rather to voluntary demand-side responses,” Dave et al. note. Even without lockdowns, in other words, businesses would have suffered as consumers afraid of catching COVID-19 reduced their excursions and spending.

Likewise, Abbott’s remaining COVID-19 restrictions were hardly the only obstacle to a full economic recovery in Texas. “Too many Texans have been sidelined from employment opportunities,” Abbott said when he announced the reopening. “Too many small business owners have struggled to pay their bills. This must end. It is now time to open Texas 100 percent.” Contrary to the implication that the March 10 reopening would reduce unemployment, Dave et al. found no evidence that it did.